Paul’s original name was Saul. He was a full-blooded Jew, born in Tarsus in south-east Asia Minor ( Acts 9:11; Acts 22:3; Philippians 3:5). He inherited from birth the privilege of Roman citizenship ( Acts 16:37; Acts 22:26-28), and he grew up to speak, read and write Greek and Hebrew fluently ( Acts 21:37; Acts 21:40). The Greek influence in his education gave him the ability to think clearly and systematically, and the Hebrew influence helped to create in him a character of moral uprightness ( Philippians 3:6).

Apostle Paul was a Jew; he was born at Tarsus, in Cilicia; and he inherited the Roman citizenship. In these three clauses is indicated his connexion with the three great influences of the ancient world- the religion of Palestine, the language and culture of Greece, and the government of Rome.

In his case the first of these was the oldest and the deepest influence. We hear little or nothing of his parents; a sister’s son intervened at one point with good effect in his earthly fortunes; but all the indications suggest that he was reared in a religious home. He speaks of himself as ‘circumcised the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee’ ( Philippians 3:5); and these terms betoken an intensely Jewish atmosphere. Still, he was born not in the land of the Jews, but in the territory of the heathen. Cilicia was not very far from Palestine; but any heathen country was ‘far off’ in a sense other than local. This distance St. Paul was sure to feel; yet he could boast of his birthplace as being ‘no mean city’ ( Acts 21:39). It was beautifully situated at the foot of the Cilician hills and at the mouth of the Catarrhactes; it was a place of cosmopolitan trade; and it was a university city-the very place in which the man should be born whose destiny it was to be to break down ‘the middle wall of partition’ ( Ephesians 2:14) and become the Apostle of the Gentiles. A freer air blew round his head from the first than if he had been born at Jerusalem.

There were several ways in which the Roman citizenship could be acquired, and it is not known through which of these it came into St. Paul’s family; but he was ‘freeborn’ ( Acts 22:28). Even to a Jewish boy of sensitive nature this would impart a certain self-consciousness; but it was to become of enormous consequence in his subsequent career, probably even saving his life.

In youth St. Paul learned the trade of tent-making, this being, it would appear, the characteristic industry of Cilicia, where a coarse haircloth was manufactured on a large scale, to be used for tents and other purposes. This circumstance might be supposed to indicate that he belonged to the lower class of the population. But it is said that among the Jews it was the custom at that time for even the sons of the wealthy to acquire skill in some manual art, as a resource against the possible caprices of fortune; and, in the sequel, the possession of this handicraft proved of eminent service to St. Paul, enabling him to earn his bread by the labour of his hands, when it was not expedient to accept support from those to whom he preached the gospel. Ramsay (St. Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen, p. 311 ff.) has accumulated evidence to prove that St. Paul’s relatives were persons of substance and social standing, and he considers himself able to show that, in later life, he came into possession of an inheritance, by which he was enabled to defray the heavy expenses of his trials before the Roman courts. Evidence more convincing of social standing is supplied by the fact that St. Paul was a member of the Sanhedrin, if this can be inferred with certainty from the statement in Acts 26:10 that, when the followers of Jesus were put to death, he gave his ‘vote’ against them. It is frequently stated that members of the Sanhedrin had to be married men, and from this the inference has been drawn that he was married in youth. If so, his wife must have died early, as there is no hint of a wife in the records of his life, the fancy that he married Lydia and addressed her in the Epistle to the Philippians as ‘true yokefellow’ being ridiculous, though it goes back as far as Eusebius (HE_ iii. 30) and has been revived in recent times by E. Renan (Saint Paul, 1869, p. 115).

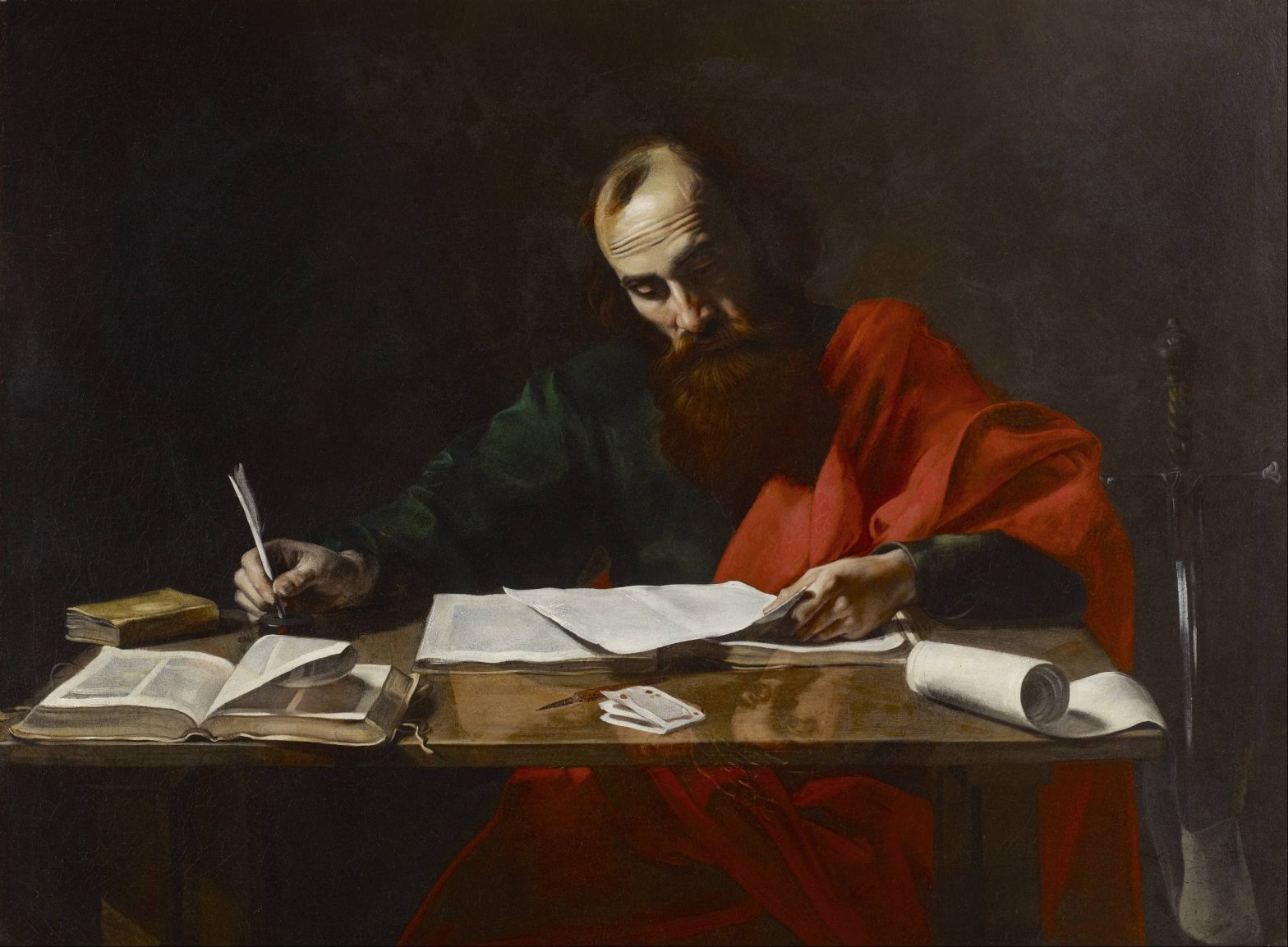

So comparatively near to Jerusalem was Tarsus that, as a boy, St. Paul may have been taken by his parents to one of the annual feasts, as Jesus was at the age of twelve; and from the experience of the boy from Nazareth we may infer what were the feelings of this other Jewish boy at the first sight of the Holy City. It cannot have been very long afterwards that he was sent thither, to reside in the place, learning to be a Rabbi. Along with other aspirants to the same office he sat ‘at the feet of Gamaliel’ ( Acts 22:3), whose intervention in the Book of Acts on the side of clemency and common sense is probably intended to be looked upon as a characteristic act. But, whatever else the disciple may have learned from this master in Israel, he did not copy this trait of his character; for the first thing we hear of him after the termination of his education is his persecution of the Christians.

There seems little doubt that Jesus and St. Paul were treading the soil of Palestine at the same time; and it is an old question whether they ever crossed each other’s path. Though Weiss (Paulus und Jesus, 1910) and Ramsay (The Teaching of Paul, p. 21 ff.) have recently attempted to make it probable that they did, there is little to be said for this view of the case. It is argued, indeed, that on the way to Damascus St. Paul could not have recognized Jesus, if he had not been already familiar with His appearance. But he did not recognize Him by sight: he had to ask, ‘Who art thou, Lord?,’ and it was only through the hearing of the ear that he ascertained who was speaking. It is true that, in one place, St. Paul demands, ‘Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?’ ( 1 Corinthians 9:1), but the sight referred to was that on the way to Damascus.