Philippi was a city of Macedonia about nine miles from the sea, to the northwest of the island of Thasos, which is twelve miles distant from its port Neapolis, the modern Kavalla. It was named after Philip of Macedon (the father of Alexander the Great), who conquered it about 356 BC and made it into one of one of his frontier strongholds.

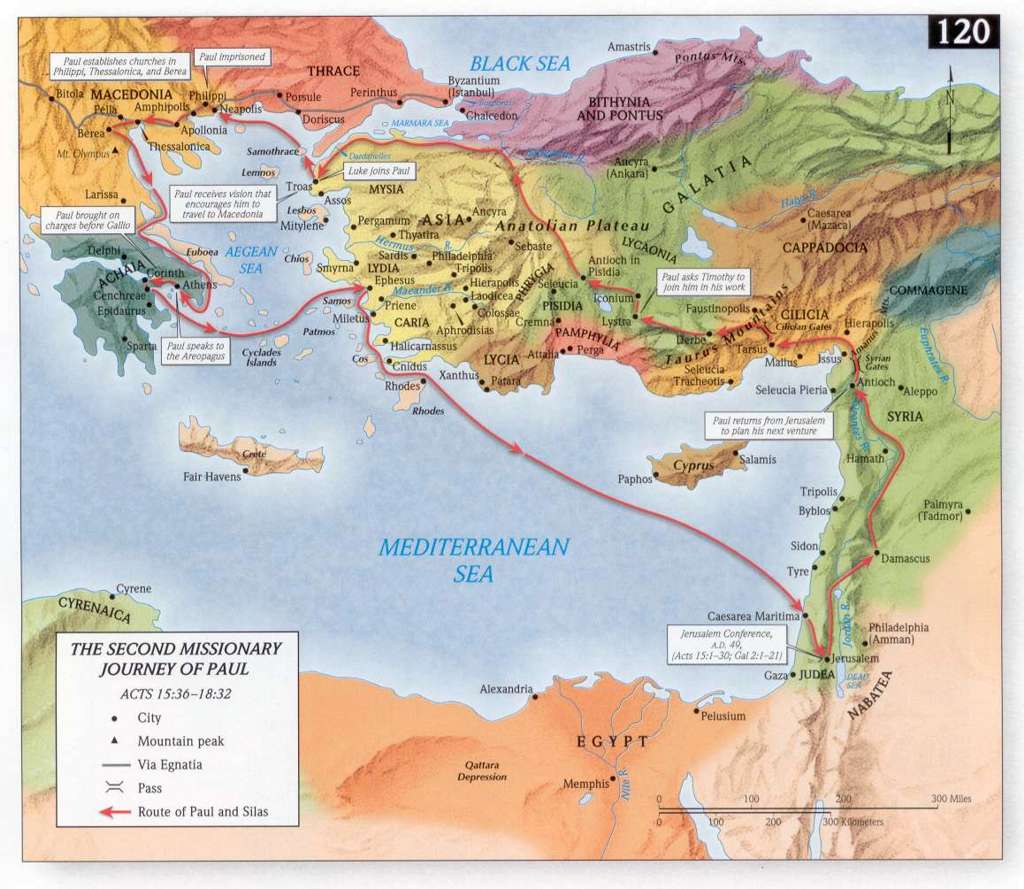

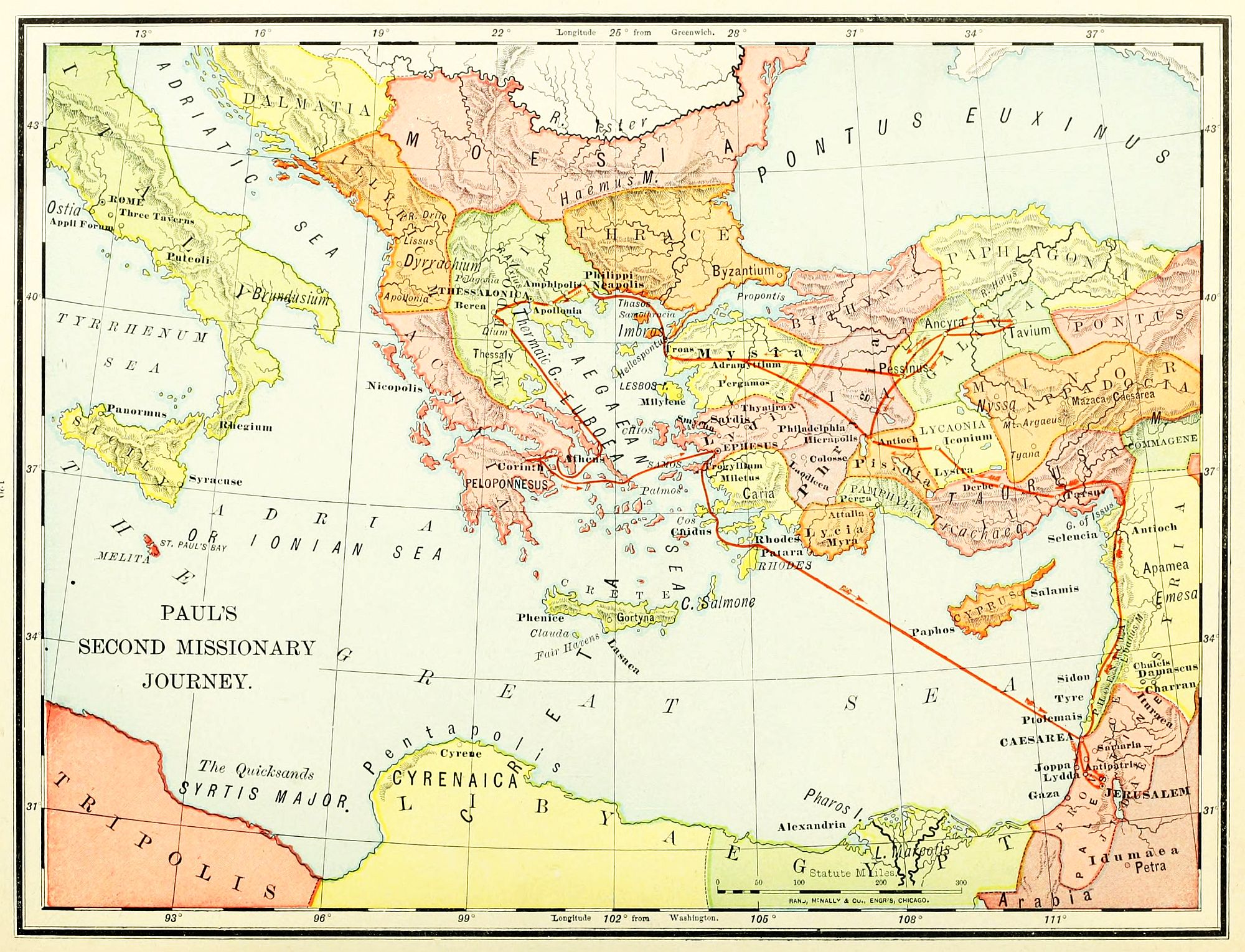

The church at Philippi was the first Christian church in Europe, planted by the apostle Paul on his second missionary journey around AD 50 or 51, in response to his Macedonian vision ( Acts 16:9 ).

1. Position and Name:

A city of Macedonia, situated in 41o 5´ North latitude and 24o 16´ East longitude. It lay on the Egnatian Road, 33 Roman miles from Amphipolis and 21 from Acontisma, in a plain bounded on the East and North by the mountains which lie between the rivers Zygactes and Nestus, on the West by Mt. Pangaeus, on the South by the ridge called in antiquity Symbolum, over which ran the road connecting the city with its seaport, Neapolis (which see), 9 miles distant.

This plain, a considerable part of which is marshy in modern, as in ancient, times, is connected with the basin of the Strymon by the valley of the Angites, which also bore the names Gangas or Gangites (Appian, Bell . 104 . iv. 106), the modern Anghista.

The ancient name of Philippi was Crenides, so called after the springs which feed the river and the marsh; but it was re-founded by Philippians 2 of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, and received his name.

2. History:

Appian and Harpocration say that Crenides was afterward called Daton, and that this name was changed to Philippi, but this statement is open to question, since Daton, which became proverbial among the Greeks for good fortune, possessed, “admirably fertile territory, a lake, rivers, dockyards and productive gold mines,” whereas Philippi lies, as we have seen, some 9 miles inland. Many modern authorities, therefore, have placed Daton on the coast at or near the site of Neapolis. On the whole, it seems best to adopt the view of Heuzey that Daton was not originally a city, but the whole district which lay immediately to the East of Mt. Pangaeus, including the Philippian plain and the seacoast about Neapolis. On the site of the old foundation of Crenides, from which the Greek settlers had perhaps been driven out by the Thracians about a century previously, the Thasians in 360 Bc founded their colony of Daton with the aid of the exiled Athenian statesman Callistratus, in order to exploit the wealth, both agricultural and mineral, of the neighborhood. To Philip, who ascended the Macedonian throne in 359 BC, the possession of this spot seemed of the utmost importance. Not only is the plain itself well watered and of extraordinary fertility, but a strongly-fortified post planted here would secure the natural land-route from Europe to Asia and protect the eastern frontier of Macedonia against Thracian inroads. Above all, the mines of the district might meet his most pressing need, that of an abundant supply of gold. The site was therefore seized in 358 BC, the city was enlarged, strongly fortitled, and renamed, the Thasian settlers either driven out or reinforced, and the mines, worked with characteristic energy, produced over 1,000 talents a year and enabled Philip to issue a gold currency which in the West soon superseded the Persian darics. The revenue thus obtained was of inestimable value to Philip, who not only used it for the development of the Macedonian army, but also proved himself a master of the art of bribery. His remark is well known that no fortress was impregnable to whose walls an ass laden with gold could be driven. Of the history of Philippi during the next 3 centuries we know practically nothing. Together with the rest of Macedonia, it passed into the Roman hands after the battle of Pydna (168 BC), and fell in the first of the four regions into which the country was then divided (Livy xlv. 29). In 146 the whole of Macedonia was formed into a single Roman province. But the mines seem to have been almost, if not quite, exhausted by this time, and Strabo (vii. 331 fr. 41) speaks of Philippi as having sunk by the time of Caesar to a “small settlement” ( κατοικία μικρά , katoikı́a mikrá ). In the autumn of 42 Bc it witnessed the death-struggle of the Roman republic. Brutus and Cassius, the leaders of the band of conspirators who had assassinated Julius Caesar, were faced by Octavian, who 15 years later became the Emperor Augustus, and Antony. In the first engagement the army of Brutus defeated that of Octavian, while Antony’s forces were victorious over those of Cassius, who in despair put an end to his life. Three weeks later the second and decisive conflict took place. Brutus was compelled by his impatient soldiery to give battle, his troops were routed and he himself fell on his own sword. Soon afterward Philippi was made a Roman colony with the title Colonia Iulia Philippensis . After the battle of Actium (31 BC) the colony was reinforced, largely by Italian partisans of Antony who were dispossessed in order to afford allotments for Octavian’s veterans (Dio Cassius li. 4), and its name was changed to Colonia Augusta Iulia (Victrix) Philippensium: It received the much-coveted iusItalicum ( Digest L. 15,8, 8), which involved numerous privileges, the chief of which was the immunity of its territory from taxation.

3. Paul’s First Visit:

In the course of his second missionary journey Paul set sail from Troas, accompanied by Silas (who bears his full name Silvanus in 2 Corinthians 1:19; 1 Thessalonians 1:1; 2 Thessalonians 1:1 ), Timothy and Luke, and on the following day reached Neapolis ( Acts 16:11 ).

Thence he journeyed by road to Philippi, first crossing the pass some 1,600 ft. high which leads over the mountain ridge called Symbolum and afterward traversing the Philippian plain. Of his experiences there we have in Acts 16:12-40 a singularly full and graphic account. On the Sabbath, presumably the first Sabbath after their arrival, the apostle and his companions went out to the bank of the Angites, and there spoke to the women, some of them Jews, others proselytes, who had come together for purposes of worship.

One of these was named Lydia, a Greek proselyte from Thyatira, a city of Lydia in Asia Minor, to the church of which was addressed the message recorded in Revelation 2:18-29. She is described as a “seller of purple” ( Acts 16:14 ), that is, of woolen fabrics dyed purple, for the manufacture of which her native town was famous. Whether she was the agent in Philippi of some firm in Thyatira or whether she was carrying on her trade independently, we cannot say; her name suggests the possibility that she was a freedwoman, while from the fact that we hear of her household and her house ( Acts 16:15; compare Acts 16:40 ), though no mention is made of her husband, it has been conjectured that she was a widow of some property. She accepted the apostolic message and was baptized with her household ( Acts 16:15 ), and insisted that Paul and his companions should accept her hospitality during the rest of their stay in the city. See further Lydia .

All seemed to be going well when opposition arose from an unexpected quarter. There was in the town a girl, in all probability a slave, who was reputed to have the power of oracular utterance. Herodotus tells us (vii. III) of an oracle of Dionysus situated among the Thracian tribe of the Satrae, probably not far from Philippi; but there is no reason to connect the soothsaying of this girl with that worship. In any case, her masters reaped a rich harvest from the fee charged for consulting her. Paul, troubled by her repeatedly following him and those with him crying, “These men are bondservants of the Most High God, who proclaim unto you a way of salvation” ( Acts 16:17 margin), turned and commanded the spirit in Christ’s name to come out of her. The immediate restoration of the girl to a sane and normal condition convinced her masters that all prospect of further gain was gone, and they therefore seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the forum before the magistrates, probably the duumviri who stood at the head of the colony.

They accused the apostles of creating disturbance in the city and of advocating customs, the reception and practice of which were illegal for Rom citizens. The rabble of the market-place joined in the attack ( Acts 16:22 ), whereupon the magistrates, accepting without question the accusers’ statement that Paul and Silas were Jews ( Acts 16:20 ) and forgetting or ignoring the possibility of their possessing Rom citizenship, ordered them to be scourged by the attendant lictors and afterward to be imprisoned.

In the prison they were treated with the utmost rigor; they were confined in the innermost ward, and their feet put in the stocks. About midnight, as they were engaged in praying and singing hymns, while the other prisoners were listening to them, the building was shaken by a severe earthquake which threw open the prison doors. The jailer, who was on the point of taking his own life, reassured by Paul regarding the safety of the prisoners, brought Paul and Silas into his house where he tended their wounds, set food before them, and, after hearing the gospel, was baptized together with his whole household ( Acts 16:23-34 ).

On the morrow the magistrates, thinking that by dismissing from the town those who had been the cause of the previous day’s disturbance they could best secure themselves against any repetition of the disorder, sent the lictors to the jailer with orders to release them. Paul refused to accept a dismissal of this kind. As Rom citizens he and Silas were legally exempt from scourging, which was regarded as a degradation ( 1 Thessalonians 2:2 ), and the wrong was aggravated by the publicity of the punishment, the absence of a proper trial and the imprisonment which followed ( Acts 16:37 ).

Doubtless Paul had declared his citizenship when the scourging was inflicted, but in the confusion and excitement of the moment his protest had been unheard or unheeded. Now, however, it produced a deep impression on the magistrates, who came in person to ask Paul and Silas to leave the city. They, after visiting their hostess and encouraging the converts to remain firm in their new faith, set out by the Egnatian Road for Thessalonica ( Acts 16:38-40 ). How long they had stayed in Philippi we are not told, but the fact that the foundations of a strong and flourishing church had been laid and the phrase “for many days” ( Acts 16:18 ) lead us to believe that the time must have been a longer one than appears at first sight. Ramsay ( St. Paul the Traveler , 226) thinks that Paul left Troas in October, 50 AD, and stayed at Philippi until nearly the end of the year; but this chronology cannot be regarded as certain.

Several points in the narrative of these incidents call for fuller consideration. (1) We may notice, first, the very small part played by Jews and Judaism at Philippi.

There was no synagogue here, as at Salamis in Cyprus ( Acts 13:5 ), Antioch in Pisidia ( Acts 13:14 , Acts 13:43 ), Iconium ( Acts 14:1 ), Ephesus ( Acts 18:19 , Acts 18:26; Acts 19:8 ), Thessalonica ( Acts 17:1 ), Berea ( Acts 17:10 ), Athens ( Acts 17:17 ) and Corinth ( Acts 18:4 ). The number of resident Jews was small, their meetings for prayer took place on the river’s bank, the worshippers were mostly or wholly women ( Acts 16:13 ), and among them some, perhaps a majority, were proselytes. Of Jewish converts we hear nothing, nor is there any word of Jews as either inciting or joining the mob which dragged Paul and Silas before the magistrates. Further, the whole tone of the epistle. to this church seems to prove that here at least the apostolic teaching was not in danger of being undermined by Judaizers. True, there is one passage ( Philippians 3:2-7 ) in which Paul denounces “the concision,” those who had “confidence in the flesh”; but it seems “that in this warning he was thinking of Rome more than of Philippi; and that his indignation was aroused rather by the vexatious antagonism which there thwarted him in his daily work, than by any actual errors already undermining the faith of his distant converts” (Lightfoot).

(2) Even more striking is the prominence of the Rom element in the narrative. We are here not in a Greek or Jewish city, but in one of those Rom colonies which Aulus Gellius describes as “miniatures and pictures of the Rom people” ( Noctes Atticae , xvi. 13).

In the center of the city is the forum ( ἀγορά , agorá , Acts 16:19 ), and the general term “magistrates” (ἄρχοντες , árchontes , English Versions of the Bible, “rulers,” Acts 16:19 ) is exchanged for the specific title of praetors ( στρατηγοί , stratēgoı́ , English Versions of the Bible “magistrates,” Acts 16:20 , Acts 16:22 , Acts 16:35 , Acts 16:36 , Acts 16:38 ); these officers are attended by lictors (ῥαβδοῦχοι , rhabdoúchoi , English Versions “sergeants,” Acts 16:35 , Acts 16:38 ) who bear the fasces with which they scourged Paul and Silas (ῥαβδίζω , rhabdı́zo , Acts 16:22 ). The charge is that of disturbing public order and introducing customs opposed to Roman law ( Acts 16:20 , Acts 16:21 ), and Paul’s appeal to his Roman civitas ( Acts 16:37 ) at once inspired the magistrates with fear for the consequences of their action and made them conciliatory and apologetic ( Acts 16:38 , Acts 16:39 ). The title of praetor borne by these officials has caused some difficulty. The supreme magistrates of Roman colonies, two in number, were called duoviri or duumviri ( iuri dicundo ), and that this title was in use at Philippi is proved by three inscriptions (Orelli, Number 3746; Heuzey, Mission archeologique , 15, 127). The most probable explanation of the discrepancy is that these magistrates assumed the title Of praetor , or that it was commonly applied to them, as was certainly the case in some parts of the Roman world (Cicero De lege agraria ii. 34; Horace Sat . i. 5, 34; Orelli, Number 3785).

(3) Ramsay ( St. Paul the Traveler , 200 ff) has brought forward the attractive suggestion that Luke was himself a Philippian, and that he was the “man of Macedonia” who appeared to Paul at Troas with the invitation to enter Macedonia ( Acts 16:9 ).

In any case, the change from the 3to the 1st person in Acts 16:10 marks the point at which Luke joined the apostle, and the same criterion leads to the conclusion that Luke remained at Philippi between Paul’s first and his third visit to the city (see below). Ramsay’s hypothesis would explain ( a ) the fullness and vividness of the narrative of Acts 16:11-40; ( b ) the emphasis laid on the importance of Philippi ( Acts 16:12 ); and ( c ) the fact that Paul recognized as a Macedonian the man whom he saw in his vision, although there was nothing either in the language, features or dress of Macedonians to mark them out from other Greeks. Yet Luke was clearly not a householder at Philippi ( Acts 16:15 ), and early tradition refers to him as an Antiochene (see, however, Ramsay, in the work quoted 389 f).

(4) Much discussion has centered round the description of Philippi given in Acts 16:12 . The reading of Codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, Ephraemi, etc., followed by Westcott and Hort, The New Testament in Greek, the Revised Version (British and American), etc., is:

ἤτις ἐστὶν πρώτη τῆς μερίδος Μακεδονίας πόλις κολωνία , hḗtis estı́n prṓtē tḗs merı́dos Makedonı́as pólis kolōnı́a . But it is doubtful whether Makedonias is to be taken with the word which precedes or with that which follows, and further the sense derived from the phrase is unsatisfactory. For prōtē must mean either (1) first in political importance and rank, or (2) the first which the apostle reached. But the capital of the province was Thessalonica, and if tēs meridos be taken to refer to the easternmost of the 4 districts into which Macedonia had been divided in 168 Bc (though there is no evidence that that division survived at this time), Amphipolis was its capital and was apparently still its most important city, though destined to be outstripped by Philippi somewhat later. Nor is the other rendering of prōtē (adopted, e.g. by Lightfoot) more natural. It supposes that Luke reckoned Neapolis as belonging to Thrace, and the boundary of Macedonia as lying between Philippi and its seaport; moreover, the remark is singularly pointless; the use of estin rather than ḗn is against this view, nor is prōtē found in this sense without any qualifying phrase. Lastly, the tēs in its present position is unnatural; in Codex Vaticanus it is placed after, instead of before, meridos , while D (the Bezan reviser) reads κεφαλἡ τῆς Μακεδονιας , kephalḗ tḗs Makedonı́as . Of the emendations which have been suggested, we may notice three: ( a ) for meridos Hort has suggested Pierı́dos , “a chief city of Pierian Macedonia”; ( b ) for prōtē tēs we may read prōtēs , “which belongs to the first region of Macedonia”; ( 100 ) meridos may be regarded as a later insertion and struck out of the text, in which case the whole phrase will mean, “which is a city of Macedonia of first rank” (though not necessarily the first city).

4. Paul’s Later Visits:

Paul and Silas, then, probably accompanied by Timothy (who, however, is not expressly mentioned in Acts between Acts 16:1 and Acts 17:14 ), left Philippi for Thessalonica, but Luke apparently remained behind, for the “we” of Acts 16:10-17 does not appear again until Acts 20:5 , when Paul is once more leaving Philippi on his last journey to Jerusalem.

The presence of the evangelist during the intervening 5 years may have had much to do with the strength of the Philippian church and its stealfastness in persecution ( 2 Corinthians 8:2; Philippians 1:29 , Philippians 1:30 ). Patti himself did not revisit the city until, in the course of his third missionary journey, he returned to Macedonia, preceded by Timothy and Erastus, after a stay of over 2 years at Ephesus ( Acts 19:22; Acts 20:1 ). We are not definitely told that he visited Philippi on this occasion, but of the fact there can be little doubt, and it was probably there that he awaited the coming of Titus ( 2 Corinthians 2:13; 2 Corinthians 7:5 , 2 Corinthians 7:6 ) and wrote his 2nd Epistle to the Corinthians ( 2 Corinthians 8:1 ff; 2 Corinthians 9:2-4 ).

After spending 3 months in Greece, whence he intended to return by sea to Syria, he was led by a plot against his life to change his plans and return through Macedonia ( Acts 20:3 ). The last place at which he stopped before crossing to Asia was Philippi, where he spent the days of unleavened bread, and from (the seaport of) which he sailed in company with Luke to Troas where seven of his companions were awaiting him ( Acts 20:4-6 ).

It seems likely that Paul paid at least one further visit to Philippi in the interval between his first and second imprisonments. That he hoped to do so, he himself tells us ( Philippians 2:24 ), and the journey to Macedonia mentioned in 1 Timothy 1:3 would probably include a visit to Philippi, while if, as many authorities hold, 2 Timothy 4:13 refers to a later stay at Troas, it may well be connected with a further and final tour in Macedonia. But the intercourse between the apostle and this church of his founding was not limited to these rare visits.

During Paul’s first stay at Thessalonica he had received gifts of money on two occasions from the Philippian Christians ( Philippians 4:16 ), and their kindness had been repeated after he left Macedonia for Greece ( 2 Corinthians 11:9; Philippians 4:15 ).

Again, during his first imprisonment at Rome the Philippians sent a gift by the hand of one of their number, Epaphroditus ( Philippians 2:25; Philippians 4:10 , Philippians 4:14-19 ), who remained for some time with the apostle, and finally, after a serious illness which nearly proved fatal ( Philippians 2:27 ), returned home bearing the letter of thanks which has survived, addressed to the Philippian converts by Paul and Timothy ( Philippians 1:1 ). The latter intended to visit the church shortly afterward in order to bring back to the imprisoned apostle an account of its welfare ( Philippians 2:19 , Philippians 2:23 ), but we do not know whether this plan was actually carried out or not.

We cannot, however, doubt that other letters passed between Paul and this church besides the one which is extant, though the only reference to them is a disputed passage of Polycarp’s Epistle to the Philippians (iii. 2), where he speaks of “letters” ( ἐπιστολαί , epistolaı́ ) as written to them by Paul (but see Lightfoot’s note on Philippians 3:1 ).

5. Later History of the Church:

After the death of Paul we hear but little of the church or of the town of Philippi. Early in the 2nd century Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, was condemned as a Christian and was taken to Rome to be thrown to the wild beasts. After passing through Philadelphia, Smyrna and Troas, he reached Philippi. The Christians there showed him every mark of affection and respect, and after his departure wrote a letter of sympathy to the Antiochene church and another to Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, requesting him to send them copies of any letters of Ignatius which he possessed. This request Polycarp fulfilled, and at the same time sent a letter to the Philippians full of encouragement, advice and warning. From it we judge that the condition of the church as a whole was satisfactory, though a certain presbyter, Valens, and his wife are severely censured for their avarice which belied their Christian profession. We have a few records of bishops of Philippi, whose names are appended to the decisions of the councils held at Sardica (344 AD), Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), and the see appears to have outlived the city itself and to have lasted down to modern times (Le Quien, Oriens Christ ., II, 70; Neale, Holy Eastern Church , I, 92). Of the destruction of Philippi no account has come down to us. The name was perpetuated in that of the Turkish hamlet Felibedjik , but the site is now uninhabited, the nearest village being that of Raktcha among the hills immediately to the North of the ancient acropolis. This latter and the plain around are covered with ruins, but no systematic excavation has yet been undertaken. Of the extant remains the most striking are portions of the Hellenic and Hellenistic fortification, the scanty vestiges of theater, the ruin known among the Turks as Derekler , “the columns,” which perhaps represents the ancient thermae , traces of a temple of Silvanus with numerous rock-cut reliefs and inscriptions, and the remains of a triumphal arch ( Kiemer ).

Literature.

The fullest account of the site and antiquities is that of Heuzey and Daumet, Mission archeologique de Macedoine , chapters i through 5 and Plan A; Leake, Travels in Northern Greece , III, 214-25; Cousinery, Voyage dana la Macedoine , II, 1 ff; Perrot, “Daton. Neapolis. Les ruines de Philippos,” in Revue archeologique , 1860; and Hackett, in Bible Union Quarterly , 1860, may also be consulted. For the Latin inscriptions see Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum , III, 1, Numbers 633-707; III, Suppl., Numbers 7337-7358; for coins, B.V. Head, Historia Numorum , 192; Catalogue of Coins in the British Museum: Macedonia , etc., 96. For the history of the Philippian church and the narrative of Acts 16:12-40 see Lightfoot, Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians , 47-65; Ramsay, St. Paul the Traveler and the Roman Citizen , 202-26; Conybeare and Howson, Life and Epistles of Paul , chapter ix; Farrar, Life and Work of Paul , chapter xxv; and the standard commentaries on the Acts – especially Blass, Acta Apostolorum – and on Philippians.